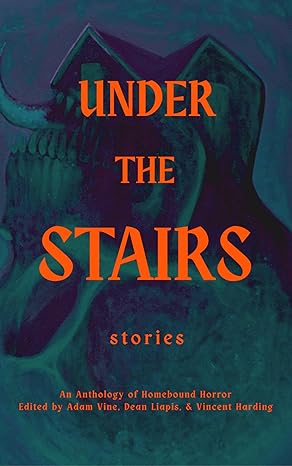

My home-based horror story “The Magpie” (penned under my pseudonym JM Connors) is coming out shortly in the Under The Stairs anthology by Ossuary Press.

It’s currently available for pre-order on Kindle, and paperbacks will become available shortly after the launch date on December 1st.

An author copy is on the way. I’ll be sure to post some photos when it arrives.

Don’t be too afraid to pick up a copy. It should be a bloody good read all around (Sorry for the awful Crypt keeper pun there. Okay, not sorry).